Translate this page into:

PROSTHODONTIC MANAGEMENT OF KNIFE-EDGE RIDGE USING CUSTOMIZED PREFABRICATED METAL MESH CUSTOM TRAY IMPRESSION TECHNIQUE

Corresponding Author : Dr. Arpit Sikri

This article was originally published by Indira Gandhi Institute of Medical Science and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Knife-edge ridge is a form of an alveolar ridge primarily caused by lateral resorption i.e. bone resorption on the buccal as well as lingual areas at a faster pace. It is usually a common clinical finding affecting the mandibular edentulous ridges; in particular, the mandibular anterior region. It can be attributed to a number of reasons i.e. the etiology is similar to the multifactorial etiology of the residual ridge resorption. The treatment options or management of knife- edge ridge generally includes a surgical and a non-surgical approach. The non-surgical approach involves the fabrication of conventional removable dentures using various modified impression materials & techniques. Prosthetic management of the patients with knife-edge ridge is a testing situation for the prosthodontist. The basic principles of retention, support, and stability are important in defining the success of a complete denture; the same can be affected in unconventional situations like knife-edge ridge. The incorporation of the conventional impression techniques may lead to an unstable and an unsatisfactory denture. Therefore, various impression materials & techniques have been proposed in literature to overcome such issues. This case report portrays an innovative and practical yet simple modified impression technique utilizing the incorporation of a customized prefabricated metal mesh into the custom tray i.e. single step impression technique using polyvinyl siloxane as the impression material of choice for managing the knife-edge ridge situation in the mandibular arch and ultimately ensuring a well-fitting prosthesis.

Keywords

Cu-Sil overdenture

Customized metal mesh impression tray

Knife-edge ridge

Modified custom tray

Sharp residual ridge

Thin ridge

INTRODUCTION:

Tooth loss is inevitable and occurs more frequently due to caries and periodontal disease. A number of secondary factors also play a vital role in loss of tooth structure1. As a part of physiological process, for example, in ageing, tooth loss becomes a regular picture. After the loss of tooth structure, the alveolar bone or the residual alveolar ridge tends to undergo remodelling, including wound repair and long-term Residual Ridge Resorption (RRR)2. RRR or bone resorption is a common, chronic, progressive, irreversible, incapacitating, debilitating, and a complex biophysical process that occurs in every patient3.

Residual ridge resorption is a term used for the diminishing quantity and quality of the residual ridge after the teeth are extracted (GPT 9)4. It is a complex process and a common occurrence following the extraction of teeth. It is most striking during the initial period of tooth loss, resulting in a slower but continuous rate of resorption thereafter5. The factors influencing the rate of resorption are divided into anatomic, metabolic, functional, and prosthetic factors6. The mean ratio of maxillary anterior RRR to mandibular anterior RRR is 1:4.2, indicating a higher RRR in mandible than in maxilla7.

The unique phenomenon of RRR can be attributed to continuous activity of osteoclasts at the surface of residual alveolar bone and occurs at a differential rate for each individual. The resorption occurring at a fast pace over the crest of the ridge leads to a flattened ridge8. On the contrary, a swift resorption of the residual ridge occurring at the buccal or the lingual areas can lead to sharp or knife-edge ridges9.

The replacement of the missing teeth and associated alveolar structures with a prosthesis helps to primarily achieve the objectives of a complete denture (CD) i.e. restoration of esthetics, function, and phonetics10. The success or performance of the complete denture relies on an accurate impression making and reproduction of the entire functional denture bearing as well as the limiting areas, easily achievable in conventional situations. Such a record helps to achieve maximum retention, support, and stability, which are the important pillars for a successful complete denture11.

Impression making is the most basic and the most important requirement for a successful CD; both esthetically and functionally. Unfortunately, in unconventional situations i.e. a knife-edge or sharp denture bearing area, certain problems or complications may arise. The main problem encountered in patients with knife-edge ridge is pain under the dentures, which is generally chronic and persistent in nature. The pain may be severe; particularly, in function i.e. during mastication12. Moreover, complete dentures fabricated over the sharp ridges can cause chronic irritation, soreness over the underlying edentulous residual ridges, and discomfort to the patient13. Wedging of the mucoperiosteum and the mucosa between the sharp, rigid spines of the ridge, and the rigid material of the prosthesis during mastication or occlusion produces irritation and pain. According to Goodsell14, razor-like or saw-tooth shaped ridges are one of the most frequent causes of discomfort from the dentures. Landa15 also listed the occurrence of denture failures as quite frequent when the mandibular ridge is thin and sharp. This may lead to difficulty in attaining the basic principles of retention, support, and stability in CD and becomes an arduous challenge for the prosthodontist in managing such situations16.

Knife-edge ridge is a form of a residual alveolar ridge primarily caused by buccolingual resorption i.e. swift lateral resorption of both the buccal as well as the lingual alveolar ridge areas17. It is usually a common clinical finding in the edentulous individuals and particularly affects the mandibular edentulous ridges i.e. mandibular anterior region18. The prevalence was found to be 89% in the mandibular edentulous region. The remaining patients had sharp ridge in the maxillary anterior region & the same has been attributed to immediate upper dentures19. As per the literature, the sharp residual ridge is rather a frequent problem among the edentulous patients who have worn dentures for long periods20.

In this location, the ridge frequently resorbs more rapidly on the labial and the lingual surfaces than it does at the crest, leaving a razor-thin wedge of bone. Knife-edge ridge can also be termed as a sharp residual ridge, razor thin ridge, saw tooth shape, thin, wiry, and sharp spiny ridge21.

A number of reasons may be attributed to the development of the knife-edge ridges. A combination of factors contribute to bone resorption, with the amount of resorption, and the relative importance of each factor varying with the patient. Etiological agents22 deemed significant include: (1) nutritional insufficiency of the diet, (2) endocrine functions, (3) tissue resistance to stress, (4) traumatic factors (dentures, etc.), (5) systemic diseases, and (6) disuse. The influence of genetic factors does not seem to have been studied. Inadequate dentures do not necessarily cause residual ridge changes in otherwise healthy individuals. On the other hand, ridge resorption probably cannot be controlled completely by ideal prosthetic procedures in a patient in whom the systemic disease or the pathologic conditions of the denture-bearing tissues exist. Immediate dentures are often an ultimate cause of sharp ridges. Moreover, it has been found that the postmenopausal women have a greater tendency to develop the knife-edge ridge in the mandibular region. Local bone destruction due to periodontal disease prior to tooth extraction, improper alveolar bone surgical procedures at the time of tooth extraction, lack of follow-up, and proper correction of changing tissue conditions, may be the factors that contribute to bone resorption23.

Management of the knife-edge ridge involves various treatment approaches or options. Broadly, such modalities may include a surgical and a non-surgical approach24. The surgical modality includes the pre-prosthetic surgery, which may lead to surgical trauma along with destruction of the stabilizing bone. The other treatment approach involves implant retained fixed or removable prosthesis. This involves the dental implant taking support from the underlying bone. In addition to this, the thin bone structure may be removed prior to implant placement for better adaptation of the same. Different sizes of implant fixtures may be required due to difficulty in determining the accurate ridge before the osteotomy. The limitations of the surgical as well as implant intervention include patient's will to undergo the surgical treatment, age and medical condition of the patient, time involved in completion of the procedure, inconvenience, discomfort, risk of surgical complications, dental implant failures, predictability of the treatment, and economics involved25. The nonsurgical or the prosthodontic approach involves the conventional prosthodontics without the surgical intervention. This involves fabrication of a complete denture over the knife-edge ridge using appropriate impression materials and techniques. Apart from the various impression approaches, balancing of the occlusal forces is also employed26.

The present case report describes an innovative and practical yet simple modified impression technique utilizing the incorporation of a customized prefabricated metal mesh into the custom tray i.e. single step impression technique using polyvinyl siloxane as the impression material of choice for managing the knife-edge ridge situation in the mandibular arch and ultimately ensuring a well-fitting prosthesis.

CASE REPORT:

A 25-year old partially edentulous male patient reported to the Department of Prosthodontics, Crown & Bridge and Oral Implantology, with a chief complaint of difficulty in eating food due to missing teeth, since 2 years previously. Patient had insignificant past medical history. Past dental history of the patient revealed that the patient was not wearing any prosthesis.

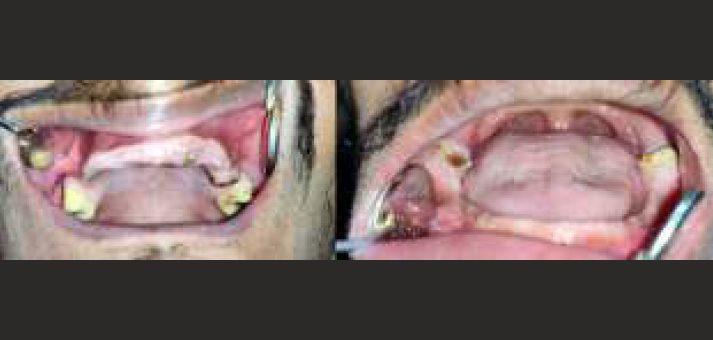

Radiographic examination revealed root canal treatment done in 22, 24, 38, and 48. Intraoral examination revealed that the patient was partially edentulous with only 18, 22, 24, and 28 present in the maxillary arch and 38 and 48 present in the mandibular arch [Figure 1].

- Partially edentulous maxillary & mandibular edentulous ridge

The patient was informed about various treatment options i.e. surgical intervention, implant supported fixed and removable prosthesis, and conventional prosthodontic rehabilitation. As there was minimal crown portion of the tooth w.r.t. 22, 24, 38, and 48, which could not be taken as an abutment for the fixed prosthesis, it was decided to retain the roots which were not infected, hence non-vital root submergence treatment was planned for the patient. After explaining the various prosthetic treatment options to the patient and keeping in view his non-willingness for the surgical modalities along with his financial constraints, a final treatment plan was chosen for the patient. This included fabrication of a maxillary Cu-Sil overdenture i.e. a combination of maxillary Cu-Sil denture w.r.t. 18 & 28 as abutment teeth with an overdenture using submerged non-vital roots w.r.t. 22 & 24 and mandibular overdenture using submerged non-vital roots w.r.t. 38 & 48. The present case report involves an innovative and practical yet simple modified impression technique utilizing the incorporation of a customized prefabricated metal mesh into the custom tray i.e. single step impression technique using polyvinyl siloxane as the impression material of choice for managing the knife-edge ridge in the mandibular arch. Informed consent was taken from the patient.

PROCEDURE:

The preliminary steps of complete denture fabrication remained the same.

Diagnostic impressions were made using additional silicone putty (GC Flexceed Putty, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). This was followed by preliminary impressions of the maxillary and the mandibular arches using additional silicone putty & light body (GC Flexceed Putty & Light Body, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) [Figure 2] in a single step. The elastomeric impression using putty & light body was preferred over the other conventional impression materials due to better reproduction of the details.

This was followed by fabrication of a primary cast using type II dental plaster (GypRock plaster, Rajkot, Gujarat, India). The outline of the knife- edge ridge area was marked over the preliminary cast [Figure 3].

A proper relief & spacer was planned & designed using an innovative method. This involved the application of an additional silicone putty (GC Flexceed Putty, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) as a spacer in comparison to the conventionally used wax spacers.

After the adaptation of the putty spacer, a prefabricated metal mesh (MAARC - CE Reinforcement Golden Mesh, Shiva Products, Thane, India) was customized (cut into a small section) and adapted over the area of knife-edge ridge [Figure 4]. This was followed by fabrication of custom (individual) trays using autopolymerizing acrylic resin (DPI RR Cold Cure, Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India). The occlusal surface of the mandibular individual tray shows the customized prefabricated metal mesh in place [Figure 5].

Border moulding was performed using low fusing green stick compound (Pinnacle Tracing Sticks, Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India). Even after the border moulding, the customized prefabricated metal mesh was intact without any distortion [Figure 6]. Putty spacer was removed from the individual tray after the final border moulding [Figure 7]. The customized prefabricated metal mesh mandibular individual tray was evaluated in the patient's mouth [Figure 8]. Final impressions were made using medium body polyvinyl siloxane elastomeric impression material (Aquasil Ultra Medium, Dentsply India Pvt Ltd, Mumbai, India). The occlusal surface of the mandibular individual tray signified that the final impression was properly flown from the customized prefabricated metal mesh area [Figure 9].

Beading and boxing of the final impressions was done to retrieve well-formed master casts. Definitive casts were poured using type IV gypsum product i.e. die stone (GypRock Dental Stone Class IV, Rajkot, Gujarat, India).

After the definitive casts were obtained, temporary denture bases and occlusal rims were fabricated.

Orientation jaw relation was recorded using facebow (HanauTM Springbow, Whip Mix, Kentucky, USA) followed by transfer to the semiadjustable articulator (HanauTM Wide-Vue, Whip Mix, Kentucky, USA).

Tentative jaw relations were carried out following the facebow transfer. After recording the centric jaw relation record, the casts were mounted in a semiadjustable articulator. The artificial teeth were adjusted and teeth arrangement was done following the ideal principles.

Waxed-up trial denture was assessed intraorally, to verify the function, fit, and esthetics, before its processing. This was followed by proper sealing of the trial denture base to the definitive casts followed by de-articulation from the articulator.

The flasking & the dewaxing procedures were carried out in the conventional manner for both the arches.

After the application of tin foil substitute (DPI Heat Cure Cold Mould Seal, Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India), a prefabricated metal mesh (MAARC - CE Reinforcement Golden Mesh, Shiva Products, Thane, India) was selected and adapted to the master cast. The already adjusted prefabricated metal mesh was checked on the maxillary cast for any last minute corrections in its adaptation; and the denture was packed, pressed, and processed in the conventional manner (DPI Heat Cure, Dental Products of India, Mumbai, India).

The processed dentures were retrieved and cleaned using an ultrasonic cleaner.

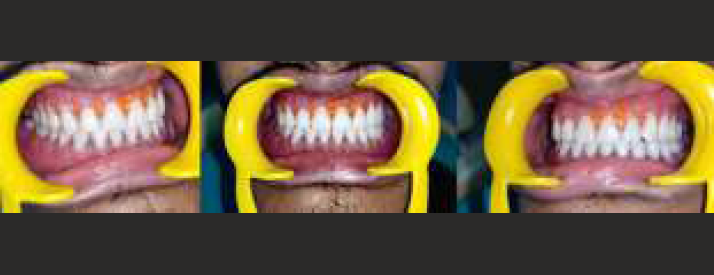

The dentures were finished, polished, and tried in the patient's mouth for evaluation of appropriate esthetics and occlusion [Figure 10]. After the necessary occlusal corrections, the prostheses i.e. maxillary Cu-Sil overdenture and mandibular overdenture were delivered [Figure 11].

Patient was given instructions following the insertion of the complete dentures. Patient was evaluated after 3 recall visits i.e. after 24 hours, 1 week, and 1 month, respectively. Patient was satisfied with the esthetics, phonetics, and function of the removable prostheses.

- Preliminary impressions - maxillary & mandibular

- Outline of the knife-edge ridge area - mandibular preliminary cast

- Prefabricated metal mesh (customization & adaptation) - mandibular

- Custom tray (mandibular) - customized prefabricated metal mesh in place

- Border moulding (mandibular) - customized prefabricated metal mesh in place

- Putty spacer removal after completion of border moulding

- Customized prefabricated metal mesh custom tray - evaluation in patient's mouth

- Final impression (mandibular) - occlusal aspect of the individual tray

- Maxillary Cu-sil overdenture & Mandibular overdenture - in patient's mouth

- Maxillary Cu-sil overdenture & Mandibular overdenture - occlusal surface & intaglio surface

DISCUSSION:

The main objectives of complete denture rehabilitation involves the restoration of function, appearance, comfort, and maintenance of the overall health of the patient. An accurate impression making is an important factor determining the stability and retention of the prosthesis. This can be very well achieved in the conventional situations27.

In unconventional situations i.e. in case of knife-edge ridge, due to lateral resorption, the residual ridge becomes thin in the buccolingual direction than in the vertical direction. Moreover, in some situations, the residual alveolar ridge may become resilient and may be replaced by an excessively movable soft tissue. This means that the flabby tissue can sometimes overly an atrophic and a knife-edge mandibular ridge28.

Patients with knife-edge ridge usually complain of pain associated with the dentures and even can point the same to the offending site. In addition to this, patients also complain of chronic, persistent soreness under the dentures; particularly, during mastication or when clenching the teeth. Dentures often lack adequate stability and retention due to improper tissue changes or repeated relief of the basal surface of the denture. Occlusal relationships are generally poor. Tissues in the affected area are usually inflamed, hyperplastic, flabby, and tender to palpation. However, many of the sharp, painful ridges are covered with normal-appearing mucous membrane. Ridges should always be palpated when examining a mouth for possible new dentures29. The production of pain by pressing the fingers on the ridge should arouse the suspicions of the dental surgeon. Meticulous diagnosis and treatment planning involving proper medical and dental history, the clinical examination, and the radiographic interpretation, ultimately contribute towards the diagnosis of the knife-edge residual ridge. The greatest aid in detecting sharp bony projections on the crest of the residual ridge is the radiographic interpretation. Three types of sharp residual ridges occur with greater frequency and can be classified according to their radiographic appearance30. These are: (1) the saw-tooth ridge, (2) the razor-like ridge, and (3) the ridge with discrete large spiny projections. However, this classification is academic because all of these types can produce pain under the dentures. Any related medical condition must be evaluated in relation to their effect on the oral structures. Before the definitive dental treatment can be successful, a medical consultation and treatment of systemic diseases must be carried out. Radiographic evaluation shows a clear, well-defined outline of thin ridge with cortical layer covering the cancellous bone31.

Various treatment modalities can be used to effectively manage the knife-edge ridges. These include the surgical and the non-surgical approach. The surgical approach includes surgical correction of the ridge to create a smooth denture-bearing surface, which can sustain a normal masticatory load without pain. Bearl32 states, "Any effort to replace a functional and aesthetic part of the human anatomy depends directly on the foundation on which it rests." This statement could involve the surgical removal of the sharp edges of the ridge. In patients in whom enough of the ridge would remain after surgery to provide adequate stability and retention of the prostheses, surgical removal of the sharp projections is definitely the treatment of choice. However, as many patients have suffered severe residual ridge atrophy, surgical treatment may leave them without any ridge. For these patients, relieving the cast or full denture over sharp ridge regions may be a temporarily effective compromise. Bolender and Swenson33 reported a successful vestibular extension procedure. This surgical technique could be used in patients who do not have adequate ridges after removing sharp projections to recreate ridge conditions conducive to stability and retention of the prosthesis. Thoma34 suggested implanting tantalum gauze or gelatine sponge on the labial aspect of the sharp ridges, especially those with undercuts, to regenerate new fullness and eliminate the need for bone removal. The use of silicone rubber has been reported for ridge extension procedures. Ridge augmentation using bone grafts can be used as an additive measure both during surgery and during placement of dental implants, but the treatment outcome remains unpredictable and debatable.

This makes the non-surgical or the prosthodontic approach as the choice of treatment modality. According to M.M. DeVan35, "the preservation of what remains is important rather than the meticulous replacement of what has been lost". The management of the unconventional knife-edge denture bearing area becomes a herculean task for the prosthodontist. Appropriate impression technique and material needs to be selected by a prosthodontist to record the knife- edge ridge in an undisplaced form with maximum retention, support, and stability. In addition to the impression making, it is critical to properly orient the occlusal plane, select a suitable occlusal scheme, and provide balanced occlusion in the patient. This can be achieved using face-bow transfer followed by arrangement of the teeth in a semi-adjustable articulator. The incorporation of improperly oriented occlusal plane along with the deflective occlusal contacts will lead to instability of the complete denture36.

The other strategies may include creating relief on the cast or in the denture over the painful regions to distribute the masticatory load all around37. The relief of the prosthesis above the sharp ridge can temporarily relieve pain. However, additional soft tissue usually proliferates to fill the space created inside the denture base. The increase in the mass of hyperplastic tissue tends to reduce the stability of the prosthesis, which can lead to a further resorption. Once again, the soft tissues are wedged between the sharp bone and an unyielding prosthesis, and the soreness returns. Tissue conditioners or soft liners are generally used for the abused and the irritated tissues. The use of soft lining materials were later discouraged due to the hygiene and maintenance issues. Moreover, it is a temporary solution for managing the knife-edge ridge situations38.

A plethora of impression techniques have been discussed in literature for overcoming the problem of the knife-edge ridge. Such techniques included the controlled-pressure impression technique & differential pressure impression technique. To simplify and overcome the limitations of the existing impression techniques, a novel impression technique was developed. This involved the incorporation of a customized prefabricated metal mesh into the mandibular custom tray and impression making using a single step impression technique with polyvinyl siloxane impression material. The aim of this technique is to produce loading onto alternative areas (buccal shelf area) and relieve the mucosa over the sharp bony ridge from the load. The areas that are capable of bearing the load should be preferentially loaded. Those areas that are incapable of load bearing should have their loads reduced39.

The differential pressure technique is associated with cutting away the impression over the sharp residual ridge with a scalpel followed by a larger perforation or numerous perforations. The controlled pressure impression technique was primarily advocated for the unemployed lower ridges. This involves relief over the mid crest area followed by impressions. The present technique overcomes the shortcomings associated with the primitive techniques used for recording the knife-edge ridges40.

The main aim of using the customized prefabricated metal mesh in the custom tray was avoidance of scalpel blade to trim the impression over the sharp ridge and avoidance of multiple perforations or escape holes by the operator. There may be a significant error associated with the creation of escape holes depending on the operator. Further, the dimensions of the escape holes may vary, hence disrupts the standardization of the impression technique. Metal mesh itself acts as a standardized approach to create multiple escape holes in providing relief, and acts as a scaffold for supporting the impression material while setting and pouring the cast. The present technique also employed a single stage impression technique involving a single customized impression tray, which can be easily fabricated. Such a technique can be easily executed. Conversely, a two-tray impression technique is more time consuming and may lead to step formation during impression making.

The impression material used in the present technique was polyvinyl siloxane because of its shorter setting time, easy mix, adequate tear strength and viscosity, extremely high accuracy, absence of any distortion on removal, ready availability, and good dimensional stability. It is definitely better over the other contemporary materials. The limitations associated with zinc oxide eugenol impression material are messiness and a variable setting time due to temperature and humidity. Eugenol is irritating to the soft tissues. This material is not elastic and can fracture in the presence of undercuts.

The technique described in this paper is not very complex i.e. it is easy to master and is easily completed and well managed even by a general dental practitioner. Moreover, neither extra time nor additional clinical visits are needed for this specialized impression technique and further the construction of a complete denture. The chairside time is minimum and the number of appointments are similar to a conventional complete denture. No extra armamentarium and auxiliary personnel is required for the impression technique. It is definitely an economical procedure.

Certain issues may be associated with this technique. This involves the tricky adaptation of the customized prefabricated metal mesh and difficulty in controlling the thickness of the impression material. In the present technique, an innovative putty spacer design was used to overcome the issues associated with the wax spacer. The incorporation of putty spacer ensures its easy removal from the metal mesh already incorporated in the custom tray prior to impression making. This is unlike in case of a conventional wax spacer, where it is difficult to remove the same; particularly, when a tin foil barrier is not used.

The advantages of the current impression technique definitely outweigh its limitations. This technique can also be employed in other unconventional edentulous ridge situations; in particular, the flabby ridge area. The modified tray design is a patient friendly approach and offers an undisplaced impression of the knife- edge ridge area with convenience.

In the present case report, the "tooth preservation" concept has been revisited. This can be proved with the prosthodontic rehabilitation modalities i.e. Cu-Sil overdentures. Cu-sil like dentures are aimed at preserving the remaining natural teeth and have a positive effect on retention and stability of the dentures. It gives the patient psychological satisfaction of retaining the natural teeth. Moreover, the over-dentures using the non-vital submerged roots help in preservation of the remaining tooth structure along with its proprioception, preservation of the alveolar bone, and additional support to the dentures apart from the mucosa.

CONCLUSION:

Management of a patient with knife-edge ridge is an arduous task and presents difficulty in fabrication of a complete denture. The other treatment options i.e. surgery and implants may be effective but not always feasible in the elderly. Conventional impressiontaking techniques pose a great challenge to the prosthodontist resulting in fabrication of a prosthesis with compromised retention and stability. CD patients can be prevented from developing sharp residual ridges and subsequent pain under the prosthesis by: (1) appropriate trimming of the alveolar ridges during extraction, (2) control of systemic disease, (3) counselling for proper diet, and (4) frequent periodic examination of dentures and oral tissues with adequate treatment of harmful conditions when present. The incorporation of the unconventional impression techniques i.e. modified impression techniques and relatively newer impression materials helps to record the knife-edge ridges effectively. Thus, the use of the modified impression technique using customized prefabricated metal mesh single custom tray and polyvinyl siloxane impression material provides an alternative, effective, and promising approach for the management of patients with knife- edge ridges.

REFERENCES:

- Complete Dentures from Planning to Problem Solving. In: Quintessence. London: Publishing; 2003. p. :123-133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Reduction of residual ridges: a major oral disease entity. J Prosthet Dent. 1971;26:266.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A Cephalometric Study of the Clinical Rest Position of the Mandible. Part II. The Variability in the Rate of Bone Loss Following the Removal of Occlusal Contacts. J Prosthet Dent. 1957;7:544-552.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms: Ninth Edition. J Prosthet Dent. 2017;117(5S):e1-e105.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The residual edentulous arches--foundation for implants and for removable dentures; some clinical considerations. A review of the literature 1954-2012. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim. 1993;2013(1):14-24. 68

- [Google Scholar]

- The Continuing Reduction of the Residual Alveolar Ridges in Complete Denture Wearers: A Mixed-Longitudinal Study Covering 25 years. J Prosthet Dent. 1972;27:120-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- " A classification of the edentulous jaws. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1988;17:232-236.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative Study of The Resorption of the Alveolar Ridges in Denture-Wearers and non-Denture-Wearers. J Am Dent Assoc. 1960;60:143-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Responses of Jaw Bone to Pressure. Gerodontology. 2004;21:65-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors of Bone Resorption of the Residual Ridge. J. Pros. Dent. 1962;12:429-440.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bone Formation and Bone Resorption, Oral Surg. Oral bled. Sr Oral Path. 1955;8:1074-1078.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practical Full Denture Prosthesis. In: Brooklyn (2). Dental Items of Interest Publishing Co.; 1958. p. :42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oral Conditions Associated With Dentures. J. Pros. Dent. 1958;8:591-599.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Complete Dentures (3). St. Louis: The C. V. hlosby Company; 1953. p. :334.

- Oral Surgery for Dental Prosthesis. In: D. Clin. North America; 1959. p. :723-733.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Management of denture patients with sharp residual ridges. J Pros. Dent. 1966;16(3):431-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bone and Bones (2). St. Louis: The C.V. Mosby Company; 1955.

- Some Clinical Factors Related to Rate of Resorption of Residual Ridges. J. Pros. Dent. 1962;12:441-450.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A local pathophysiologic mechanism of the resorption of residual ridges: prostaglandin as a mediator of bone resorption. J Prosthet Dent :198-60. 381-S

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The knife-edge tendency in the mandibular residual ridges in women. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:820-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symptomatic osteoporosis: a risk factor for residual ridge reduction of the jaws. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:656-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosssectional radiography for implant site assessment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path01. 1990;70:674-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radiologic-prosthetic planning of the surgical phase of the treatment of edentulism by osseointegrated implants: an in vitro study. J Prosthet Dent. 1991;65:541-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- "Computer tomography (CT) applications in implant dentistry." The Journal of oral implantology. 1991;17(1):10-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of computerized tomography in dental implantology. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992;7:373-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utilization of 3D/Dental software for precise implant site selection: clinical reports. Implant Dent. 1992;1:134-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presurgical tomographic assessment for dental implants. I. A modified imaging technique. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1992;7:246-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surgical preparation of the mouth for a prosthesis. J Oral Surg (Chic). 1958;16(1):3-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cephalometric Evaluation of a Labial Vestibular Extension Procedure. J. PROS. DENT. 1963;13:416-431.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oral Surgery (4). St. Louis: The C. V. Mosby Company; 1963. p. :352.

- Basic principles in impression making. 1952. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93(6):503-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonographic measurement versus mapping for determination of residual ridge width. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:358-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Injected Silastic in Ridge Extension Procedures. J. Pros. Dent. 1964;14:460-464.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Osteoclasts: what do they do and how do they do it? the American Journal of Pathology. 2007;170(2):427-435.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral Health Care - Prosthodontics, Periodontology, Biology, Research and Systemic Conditions.

- [Google Scholar]

- Residual ridge resorption in the edentulous maxila in patients with implant-supported mandibular overdentures: an 8-years retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:265-300.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]